Two queer people raise their son with a tireless conviction sculpted by trauma, conflict, and comedy.

A + Z // Matawan, New Jersey

Content warning: depression, self harm

To believe in A and Z's love story is to believe in the capacity of fate, the existence of destiny, and the authority of stars to ordain what lies in our futures.

Or, if not that, to at least believe in the algorithmic matchmaking ability of Zoe, a dating app for queer women that allows users to filter matches based on, among other traits, someone's astrological sign; Libras for Geminis, Scorpios for Cancers.

When Z downloaded the app, she looked for Tauruses, who were the most compatible with her, a Virgo. She scrolled to A's profile, and paused. A was beautiful, and quite upfront with the fact that they had a four year old son. Curious about their story, Z swiped right.

A on the wedding day

When A downloaded the app, they didn’t expect much to come from it; maybe a few flings, but no one, they thought, would really want to be with someone who already had a child. They scrolled to Z's profile, and also paused. Swiping through Z’s photos, A produced two thoughts. The first: "Wow, she's really gorgeous." The second, "But she's definitely a player." A, too, swiped right, hoping in some ways to be right, and in other ways to be wrong.

Z on the wedding day

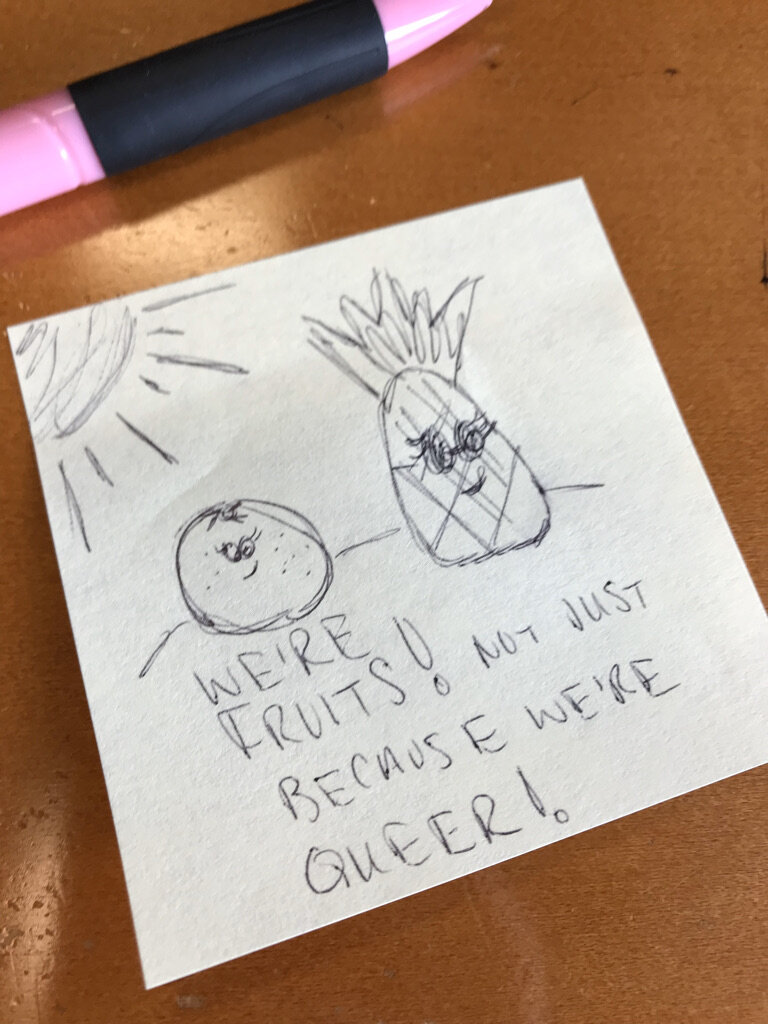

Opposite to A's player impressions, Z yearned for something meaningful; something long-term, and lasting. "I had so many pure, innocent feelings!" Z exclaimed to me with her brows furrowed but lips formed in a smile. She sent the first message to A: "What's your next big adventure?" Both were giddy as they texted back and forth, flirty and romantic, unashamed in their yearning for one another. A sent small drawings they made on their iPad, full of whimsy and color. Z, in return, sent poems about her love and their future together, full of dreams and charm.

Notes and drawings A and Z made to one another

Z and A on an early FaceTime call together

They met in-person a few days later in Somerville, New Jersey. A planned the date and, on paper, nothing went right. The original restaurant they wanted to go to was closed; A had a bout of profanity while driving to a different restaurant; their dining table was an awkward corner booth; and the drive they took after dinner to stargaze in a nearby park was entirely dark and, in hindsight, quite creepy.

But Z remembers each misstep as a moment of playful romance. The restaurant being closed made her less nervous ("I saw how embarrassed A was, and it took off some of the pressure and nerves I was feeling"), A's road rage made her laugh ("It was so easy to be with them, and hilarious that they showed me that side of themselves so soon"), she loved the awkward table ("It was perfect because now I had an excuse to sit right next to them, hip-to-hip"), and the creepy drive just became the funny lead for an intimate moment ("We shared our first kiss stargazing in that park”).

Z and A on a date

At the end of the night, as she and A parted ways at the train station, Z dreamt of a cinematic adieu: she would kiss A goodbye and jump onto the train right as its doors closed, waving from the window and leaving both of them with the fond memory of a beautiful night.

Instead, as the train slowed to a stop and its doors opened, Z turned, leaned in for a kiss, and tripped, smashing her teeth into A's.

"Oh, I forgot about that," A said with a pensive look on their face. Z and I laughed, and A also began to smile.

A and Z on a date

As A and Z shared the story of how they met, they often turned to each other; smiling, giggling, filling in details the other omitted. An unmistakable joy filled this lighter, happier conversation, one that we only reached after spending the previous hours wading through topics—depression, abuse, resentment, forgiveness—of a far heavier nature.

We laughed together, and Z mused. "We often diminish the cuter moments in our story, because the rest of it tends to overshadow those tender, butterfly feelings we had when we first met." A recalled their own memories of Z and how she fit into their life at the time. "It was so easy to be with Z. She was so cinematic, and romantic, and such a whirlwind at that time in my life."

A paused, looking for more ways to describe Z. "I thought she was very magical and... ethereal. Very siren-like and mystical. I was so enamored." They thought some more. "Oh also, she smelled really, really good."

A and Z on their wedding day

A few months after A and Z shared this story with me over a video call, I sat at their dinner table in-person as the three of us, hunched like a family of raccoons enjoying the spoils of a moonlit search for food, crunched through a large box of Taco Bell Doritos Locos tacos. A smirk spread across my face as I pictured the Z on her first date with A, a siren-like figure so full of mystery and grace and beauty, contrasted with the Z who now sat in front of me, evolved into someone more true to life and whom A loved even more but who was also, candidly, a bit less cinematic.

"This is who we really are, Vincent," Z joked as she squeezed a packet of Diablo hot sauce onto her taco. She took a large bite and her face settled into a meditative calm that obscured the hedonistic euphoria she felt indulging in this minor but rare sin.

We smiled and laughed at how much we smiled and laughed; at this trivial sign of liberty, when we ate and swore and laughed as we pleased. (Harrison, Z and A's seven year old son, was with A's mother for a few days.)

Our conversation that evening was lighter, but ordinarily, to spend time with A and Z in their home is to observe how they translate abstract values into concrete lessons for their son. A different evening, when Harrison was at home, we ate a more common meal of Korean tofu stew. At some point, our conversation lulled into a few moments of silence.

A, Z, Harrison, and I having dinner together one evening

Harrison, perhaps nervous about the quiet, asked, "Can we talk about penguins, please?" Z responded. "Sure, I'll give you two minutes to explain to me why penguins are worthy of being talked about." Harrison formed a quick reply. "Because they're cute... and they look really cute when they waddle." Z nodded approvingly. "That's so true. Great argument. Let's talk about penguins."

I asked if they'd seen March of the Penguins, the famous documentary about the absurd journey penguins go on each year to feed and mate; A was reminded of a scene from A Place Further than the Universe, an anime about a group of girls who travel to Antarctica together; Harrison, who kept repeating "Penguins are so cute!", said he'd love to "put a ginormous penguin poster in someone's locker so they could put it up in their room!"

And suddenly, our conversation swiveled towards a more significant thesis. "I don't know buddy," Z said with a tone of hesitant disapproval, "I didn't enjoy people just putting random things into my locker when I was in school." Harrison, realizing his error, tried correcting himself. "Well, I could give it to someone who really, really likes penguins, right?"

This time, A spoke. "Yeah, but you have to wait and see if somebody really loves penguins. And it's always important to ask for permission and consent from other people, you know?" Harrison nodded in response; consent and boundaries were ideas A and Z reminded him of often.

Z teaching Harrison something for school one day

After he tired of penguins, Harrison blurted, "I know how to own a theme park!" I'd been with A and Z for a few nights, and knew that it was okay to reply to their son’s random statements with level-headed sincerity. "What exactly do you mean, 'I know how to own a theme park?'" I asked, curious why he'd suddenly brought up the topic.

He hesitated. "Uh.... that's... a secret." (I found out later he'd been playing Roller Coaster Tycoon.) A, Z, and I chuckled, knowing my question had gone over his head. A few seconds later, though, Harrison came up with an answer. "I could be a billionaire! Then I could own a theme park." He smiled proudly. "We could win the lottery, like, 500 times."

And again, suddenly, our conversation dropped to unexpected depths, like the moment when the shore yields to the ocean and the ground below disappears. "Well, if we could win the lottery that much, then we would support everyone and end poverty, for good," Z said. "If you get that wealth, remember, you've got to share." Harrison nodded and, eager to show how he'd do so, replied, "I would... win the lottery for really, really good African American and Chinese food business that aren't doing so well so they can..."

He stopped, clear in the notion that a restaurant needed money to operate, less clear as to exactly why. A helped. "So they can pay rent and continue to make really good food, right?"

"Right."

Z, Harrison, and A at the wedding

A and Z continued to lead us further away from a juvenile treatment of the topic. "Remember Harrison," Z began, "people don't make billions of dollars; people take billions of dollars. So if you're making that much money, you're doing it off the backs of people who work really hard but don't get paid enough. So if you ever become a billionaire, buddy, you’ve got to make sure you pay your workers really, really, really well. $25 an hour, minimum."

"$30," A countered. Z nodded in quick agreement. "Yes, $30, at least."

The conversation gradually floated above Harrison. "He gets Chinese New Year money," Z said, "but we told him that he could only spend one third of it. He had to donate another third of it, and put the last third into savings that he couldn't take back out until college." She also mulled, half-joking, "We're like the government for him, so we could impose a family tax on whatever he gets from birthdays and stuff. What is the tax rate now for freelancers? 20%? 30%? We'll just do that."

I can only guess how much of our conversation Harrison actually followed; he looked back and forth at us as he finished his food. Z turned to him. "Here's your real step one: To become a billionaire, you have to have a great work ethic. So, please, clean the table for your elders." Harrison politely asked me if I was finished with my food, then gathered our plates and placed them into the sink.

Harrison at home one evening

I would have been more surprised by the sobriety of these conversations with and around Harrison were it not for A and Z setting a similar tone on our very first call together, back in July 2020 when they first reached out to me about their story.

After we exchanged the requisite pleasantries of a video call, I offered to answer any questions they had about my project or my work. A replied quickly. "Our questions are not necessarily about your process at this point. They're a little more personal." They paused to look at a small piece of paper where they’d written some notes. "How do you feel about everything going on right now with Black Lives Matter, and what are your thoughts on feminism?"

I was caught off-guard. Usually, couples’ first questions for me were about logistical matters, like whether I was okay sleeping on a couch or what foods I might want to eat. Never had someone immediately asked about my social views. But my surprise soon settled into deep respect, and after I gave my answers, A and Z, looking satisfied, took a few moments to explain why they felt it was so important to ask, explicitly, about issues important to them.

“We've been trying to really narrow down the people that we have in our lives, whether they're just passing through or whether they're staying,” A began. “We’ve both recently said goodbye to a couple of friendships because there was just an unwillingness to learn and grow. Especially because we want to share so much of our life with you, we definitely want to make sure that we're on the same page.”

Z chimed, "Plus, I presume it would be very difficult to photograph our wedding and to get to know us more if you turned out to be a homophobic woman-hater." Her face sprouted a small smile, trimmed with a sense of reserve that suggested she spoke not out of theoretical jest, but material pain.

A and Z with their dogs at home one evening

A made note, too, of Harrison. "Especially because we have a child in the house who is a white male, we have to set a really high standard for him of what acceptable behavior is. He doesn't watch traditional kids cartoons because a lot of them now are kind of rude in the way they portray speaking to elders and adults. So, instead, he watches a lot of feminist propaganda." They laughed as they said the last two words, signaling they meant them somewhat jokingly, and clarifying that it involved exposing him to media that represented their and Z's own experiences as queer people of color. (She gave the Michelle Obama documentary as an example.)

I quipped at how entertaining it'd be to talk to Harrison in the future about his upbringing, and how much he’d remember his parents’ efforts to impart their values. A replied, "Oh, for sure, because when he gets older, he'll look back at all of his media and definitely say, 'They made me this way.'" Z added, "Well, there's nothing wrong with making him feminist and anti-racist." A nodded in fervid agreement.

Z and A told me about how Harrison had already been teased by classmates for having two moms, and how proud they were of him for arguing back, challenging their notion it was somehow “weird.” A said, "We've told him, 'Some people have two moms, some people have two dads, some people have one mom and no dad, some people have a dad and a mom, and that's all normal.' So to him, this is just a variation of normal." Z added, "After A and I had been dating for a bit, I just told Harrison one day, 'Hey, you want a bonus mom? Then you can call me Ahma, which means mother in Cantonese.’”

Harrison embracing Z at the wedding

Harrison's childhood—well-defined, safe, full of attention and love—contrasts A's own upbringing—transitory, dangerous, and often lacking role models or affection.

"I'd like to start my story in the womb," A told me. "My father used to say how he'd met me in a dream before I was born and had written down that I'd be a girl and what I'd look like. And evidently, he was right."

A with their father

Baby A

A was born in Gunnison, Colorado and grew up traveling between their parents' small farm in the Colorado mountains and their paternal grandmother's home in Mesa, Arizona. "We had a whole bunch of chickens in Colorado," they told me, "and my paternal grandmother was a very typical southern grandma; always making biscuits and gravy, and very, very religious."

When A was seven, their parents moved the family to New Jersey to live nearer to A’s maternal grandparents in towns throughout South and Central Jersey where, as A put it, "our family was poor as fuck, and we wouldn't have been living there if it weren't for my grandparents providing our housing."

A’s parents on their wedding day

A (right) with her brother (front) and father (back)

A recalled a certain blanketing sadness from childhood. "I have these journals from when I was a kid, and I was just, like, so depressed," they told me. They remember having to be perfect for others. "My grandmother was picture perfect, the classic American grandmother. And I was her granddaughter, so I was perfect, too. And I think that was really damaging. I felt like I had to be the perfect one, or the smart one, or the one that was put together, because my immediate family was constantly falling apart." The adults in A’s life often complimented their eloquence and maturity, not aware that those traits came from the burden of caring for their family, many of whom struggled with mental health issues.

A (center) in early high school

A never felt able to express their true emotions, and their depression only grew over time. Their father passed away from a stroke in their Sophomore year of high school ("I don't know what to say about that...” A said to me, “I don't feel sad about it anymore, but it's just really... weird to see a person die in front of you in the hospital,") and after a number of more private experiences they described as simply "not ideal," they began to self-harm.

"In that period of time between middle and high school, I was hurting so much, felt so empty and unloved, unworthy. The magnitude of what I needed to do mentally to put myself together was just so overwhelming. But physically, I knew to avoid my major arteries, where the risk felt really low to be able to feel something and also put myself back together. And I think the physical pain was just so much easier to manage than the emotional pain I was going through."

I asked A if they’d ever had any conception of the future; what they might do or whom they might be. They paused for a long moment to think.

"I thought I would be dead by now. Which is really sad."

A in early high school

We had this conversation over a video call late one evening. As A shared, Z nudged herself closer, wrapping her arms around A and gently caressing their hands.

"Now I look back at those scars and I'm like, I could never do that again," A continued. “If I could go back, I'd tell myself, 'You don't have to do this. I swear on my life that it's going to be fine, and you're going to be okay.' But at the time, there was nobody. None of the adults in my life knew what to do, and no one was there to help me absorb any of the things that I was going through."

I've become more attuned, over time, to the act of finding balance in someone's story, particularly when that story involves trauma. When does emphasis on a period of time become overemphasis? Is it ever appropriate to flatten the complexity of life into a single story or emotion?

I asked A whether they had lighter moments; groups of friends to run around with, memories of childish exploration and wonder and joy. "Yeah, I definitely had a group of friends in middle and high school where we had moments just doing stupid kid shit," they replied. "And I think that was really nice." They talked of midnights sneaking out on clandestine swims in the neighborhood pool; exploring the abandoned mini golf course near a motel they once lived in; pranking their grandmother after church by placing bubble wrap under her tires. "It was definitely nice to have those moments," A said. "But, ultimately, I think those moments are overshadowed in my memory, because when they ended, I still always had to go back home. Back to what I was feeling."

A began working as soon as they could, in part to escape from home and in part to escape from childhood’s dependent clench. They got their first jobs at a sandwich shop and movie theater at age 15, and started community college when they were kicked out of their home at age 17. (They dropped out after a few months when they could no longer afford to attend.)

When they were 20, A had Harrison, and alongside their descriptions of life’s financial and emotional chaos at the time, A also talked about how they always loved, wanted, and fought for Harrison: his birth, the years when A raised him as a single mother and, more recently, when he was four, and met Z.

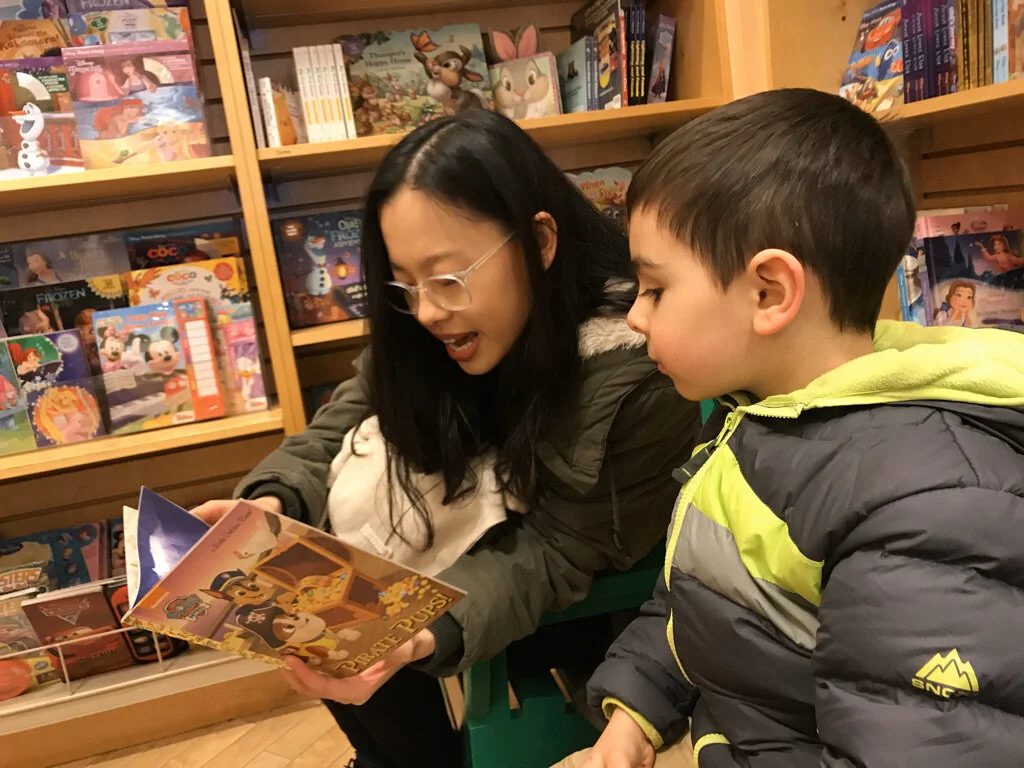

Z recalled her emotions meeting Harrison for the first time, after she and A had been dating for a short time. "I'd helped to raise my own younger brother," she told me, "so I wasn't nervous to be around a child. But I knew that meeting Harrison was a make-or-break moment in my relationship with A, because if Harrison didn't like me, then there wouldn't be a point in A having me in their life."

She told me of how intensely she wanted for her relationship with A to work out, and thus for her interactions with Harrison to be positive. "I was so fixated on just being with A, this person who made me feel everything, and who didn’t make me feel shame. I was just happy."

(Harrison, who has always been very open and talkative, took a quick liking to Z.)

Z reading to Harrison the first time they met

Z's story, like A's, begins before she was born, when her mother, who lived in Hong Kong with Z’s father, went into labor early. She was rushed to the hospital in the middle of a late summer typhoon, a frenzied metaphor for Z’s move from the warm, wet safety of the womb into the warm, wet chaos of the world.

Z’s parents believed that she would be born a boy (anyone Z's met with the same Cantonese name as her, Tsz Lok, have all been men) and even after Z was born, they treated her as an oldest son, assigning her the mantel of their expectations and ambitions.

A young Z with her father

In Hong Kong, Z's parents owned a restaurant but decided, when Z was two, to uproot their lives and move to the US in hopes that Z, and any future siblings she might have, would have a better life. They immigrated to the US in 1997. The family first lived with one of Z's aunts in New Jersey before saving enough money to rent their own apartment in Brooklyn, New York, and eventually their home in Hazlet, New Jersey. Z's father switched careers from restaurants to watch repair, while Z’s mother worked in fashion production.

Z as a child

Of her own memories from Brooklyn, Z couldn't recall much. "Everything just blurs together," she told me. She did, however, remember her parents' focus on her academic success. "My parents brought me to a daycare where all the kids were Asian," she said, "and because their parents pushed really hard on their academics, I also ended up getting pushed really hard on academics. I excelled, and because I took to it so well, that became the only validation I got."

Z continued. "I kept being a perfect child in school, because I didn't want to offend my dad or do anything wrong. I wanted to be perfect for him, and I loved him so much, because he would dote on me all the time." She recalled an early moment when she fell short of that perfection, when she was four and struggling to complete a set of math exercises at home. "I kept getting the wrong answer, and my parents got really fed up with me and kicked me out of the apartment," Z said. She described her view—“I remember seeing the warm gas-powered stove through the apartment's window”—and her emotions—“I was so scared I’d have to sleep outside that night in the cold.” "It felt like hours, even though they probably let me back in a few minutes later."

Z with her father

The milestones Z does remember all connect to the awards she won in school: a medal for a reading contest at Chinese school; a trophy for art she made in elementary school; bigger trophies for science and language awards she won in middle school. Her desire to impress others only deepened when she turned 11 and her younger brother, Nick, was born. "As the firstborn daughter of an Asian family, I suddenly had a ton of obligations and responsibilities," she told me, recalling the way she cared for Nick while her parents were busy working.

Z (center) with her brother and mother

At first, Z chafed at the prospect of spending so much time and energy caring for Nick, unable to understand why all her friends participated in attractive extracurricular activities while she was stuck babysitting her brother. But one afternoon, as she napped, Z woke up to find Nick having what looked like a seizure. He ultimately was in no harm, but the experience shook Z. "I was so freaked out, and I felt so guilty, because it felt like my inattentiveness could have killed him," she told me. From then on, she doted more on her brother and focused even more on school.

Around her, pressure built from immediate and extended family members. "All of my cousins were just starting to become doctors," she said. "They'd graduated from Ivy League schools, and were doing all this great stuff. So when I got to high school, all eyes were sort of on me, thinking, 'What amazing things is this one gonna do, because she's done well so far?'"

Z with her family in high school

She applied to High Technology High School, or simply High Tech, a public magnet school that is best known for offering advanced technology and engineering classes. Since its founding in 1991, the school has regularly ranked at or near the top of national lists for best high schools in the US. Its acceptance rate, 25%, is more selective than many universities.

To Z, her admission letter to the school represented the beginning of her next, bright chapter in life. Her experience soon turned into the opposite. "When I got there, Vincent, it was so fucking intense," she exhaled in a sharp tone of pained exhaustion. "There were aspiring Olympians, people already well-known in the world of math and science doing advanced projects since they were, like, 12. They were prodigies, and the cards were stacked against me because I had nothing special to offer. I wasn't skilled at doing anything but taking tests in school."

"I felt pressure everywhere," she continued. "I had to be special. For my parents. For the school. For my classmates so I could fit in with them doing all these amazing things. And I just felt like I wasn't." Z received a lot of (unwanted) attention from many of her peers who interpreted her inadequacies as rebellion against the stereotype of a "perfect Asian student,” even though, Z told me, "I was that. I was just failing at it."

In the moment, all she could feel was shame and fear; shame that she was struggling in the first place and fear that seeking out help would be interpreted as a sign of weakness, or worse, insanity. She coped by distracting herself with applying to college, a process that should have been filled with excitement and hope but instead contorted into dread and humiliation. Like her peers, Z aimed high, towards the Ivies and other big-name schools. But where many of her classmates applied to over 20 universities, spraying applications and praying at least one of them would be accepted, Z only had the money to apply to three: an Ivy League, The University of Chicago, and Rutgers. She was accepted at Rutgers but not the other two. "It felt like every single person in my class had been accepted to an Ivy League school except for me, and that insecurity just fueled even more shame,” she told me.

Z's time in high school prompted her to view college as a reset. "I somehow got over all that shame, I think because I was just done with feeling so shit about myself," she told me. "Everyone was shitting all over any school that wasn't an Ivy, and I was so done with high school that I cut mostly everyone out of my life and proceeded on to college from there."

Z (center) at her high school graduation

High Tech's emphasis on STEM education left little room for Z to pursue more creative interests, but college offered the chance to explore whether the artistry she'd pushed to the margins of her identity could be brought to the center. "I accidentally stumbled into landscape architecture when I took an elective class that was supposed to be an easy A,” she told me. “It seemed fun, but I never thought I could actually do art because I went to a STEM high school.”

Half of the students in her major were older than 30, and they came from a diverse swath of backgrounds. "It was really, really nice to connect with such a big range of people,” Z said. “You kind of drop all the formalities and preconceived notions about people when you're all staying up in studio together until 4am."

Always a hard worker, and no longer crushed with insecurities as in high school, Z excelled in college. She did well academically, graduating summa cum laude, and grew emotionally after an incident with personal safety. "It was a really bad situation," she told me, "and after that, I was like, Fuck this shit, I'm going to force myself to become a lot stronger and more independent so that people know that I'm my own person. I'm carving my own path, and if you're not here to do good, stay out of the fucking way."

Z with her family at college graduation

After graduation, Z traveled and reflected on how to find fulfillment for her own sake and not for others’ approval. She nurtured a desire to keep creating art and beauty and applied for an internship at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. She was surprised to receive an offer, and even more surprised to be put on their graphic design team, creating signage and flyers for exhibits and products around the museum. She loved the work, and has continued working in graphic design ever since.

A description of some of Z’s work at the MoMA

Z at the MoMA with her family

One of Z’s art pieces

Design has also yielded personal benefits for Z. "It's often been hard to communicate with words about how I'm feeling because of years of repressing my thoughts and emotions," she told me, "but graphic design and making art can be really comforting, because whatever I need to express, I can do it without saying anything."

Z on the morning of the wedding

A and Z met one another as each began to heal and grow from their past traumas. "A whole bunch of crazy shit had happened in my life," A told me, "and in that moment as things started to get less crazy, as I began to heal after all these abusive relationships I was in, I found Z. And we wound up having this really amazing connection." A had just begun redefining their sense of self-worth; Z accelerated that process. "I loved Z," they said, "and I wanted to really be the best person I could be and to show up for her. This kind of healthy and supportive relationship was really a new thing in my life."

Z and A on a trip to Arches National Park

A commented, too, on Z's growth, turning to her as they talked. "I think when I met you, Z, you were very newly who you were, and you've since grown into fully embodying the mission you were starting on at that point." I asked Z for clarification; who was this new Z, and what exactly did she embody? She replied in layers. Professionally, she was newly devoted to art; personally, she'd begun to offer her genuine self to others and to rely less on others' words of affirmation. "I will stand my ground with my beliefs now," Z said, "and I will put my beliefs at the forefront so that people can gauge where they want to be with me."

That philosophy changed how she talked with her parents, too. "I try to validate my parents with my words a lot, because I see that they needed it, too, but were deprived of it,” Z said. “I think because I deeply craved validation, and didn't quite get it, I always take the time to give others words of affirmation."

Z’s family on the wedding day

Dating also pushed A and Z to grow together, through easy moments and especially through fights. The two have, technically, four proposals: two informal, two formal. The first of the informal proposals came in August of 2018, just a few months after they first met in March 2018. One evening at Z's parents’ home, while Z washed dishes and A scrolled through their phone at the kitchen table, Z paused. "Hey," she said, not looking up from the dishes. "Do you wanna marry me?"

A didn't look up from their phone. "Sure, why not?" they replied. Z grinned, and tried calling A’s bluff. "Really? Are you sure?" "Yeah." A replied again, and both returned to their work, smiling to themselves. "There was no ring, no promises, and no kisses afterwards, so we joke that it wasn’t our real proposal story," A told me.

Z and A together at home

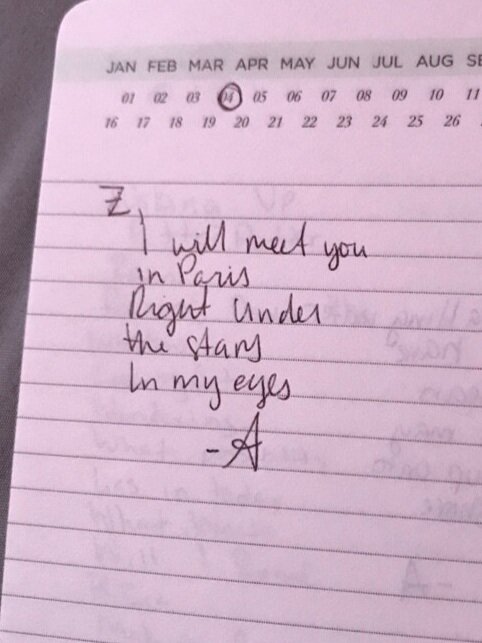

Their second informal proposal was less playful and followed a period of intense fighting. At the end of 2018, A and Z took a trip to Paris with Harrison and Z's younger brother, Nick. They fought nearly every day. Z spoke about her own communication issues. "I hate confrontation, but I also can't lie for shit, so everything's written on my face," she said. "I wasn't noticing toxic behaviors, like the silent treatment, or trying to bury things, and I'm sure it feels particularly shitty on the other end of that, because you know someone's mad, but they just won't talk to you about it. They're just putting all that bad energy onto you."

Z and A in Paris

They kept arguing when they returned from Paris. Before the trip, Z had already bought an engagement ring but, certain that A was about to break up with her, she gave the ring less as a proposal and more as a different kind of promise. "I was sure A was already halfway out the door, and so I felt like I couldn't propose to them and pressure them into marrying me," Z said. "But I still wanted to give them the assurance that I was going to love them forever and that I was gonna be there for them and Harrison, because I'd made a commitment in my heart. They really swept me off my feet, and I needed them to know how much they meant to me, even if we wouldn't be together."

Z, A, Harrison, and Z’s younger brother Nick at the Louvre in Paris

When she gave the ring to A, Z also asked if they could set a breakup date: July 2020, a year and a half later. A was shocked and angry. "I was like, ‘who picks a breakup date?" Z described a logic rooted in her love for A. "I was convinced A was already going to break up with me, so me picking a date was me trying to say, 'Please, let's at least spend more time together?’"

A, in fact, had no plans to break up with Z despite their arguments. In reflection, A and Z see their fights as an ultimate good. "We fought a lot with each other," A told me, "and I think because we stayed together through it all and worked it out, we became more gelled as a couple. Through all those fights, we truly understood who we were at our cores."

A, Z, Harrison, and their dog, Copper

Before I arrived at A and Z's home, each gave me a book recommendation that came up again during our conversations about their individual and relational traumas, and how they’ve healed in recent years.

Z shared The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang, which documents the Japanese Imperial Army’s massacre of an estimated 300,000 Chinese civilians during their siege and occupation of Nanjing, China between 1937 and 1938. A shared Legacy by Suzanne Methot, which describes in personal and historical terms the traumas Indigenous people have experienced in Canada as a result of colonization and government policy, and argues how trauma affects not just the individual who experiences it but also generations of people afterwards through altered biology and sociology.

I often texted my thoughts to A and Z as I read, commenting how, for me, the ideas in one book complemented the other. The Rape of Nanking elicited personal anger and sorrow connected to my own Chinese heritage; all four of my grandparents lived through the years before and during WWII in mainland China, and escaped to Taiwan in its aftermath during the Chinese civil war. They very well may have seen many of the atrocities Chang described in her book. Legacy, with its focus on Indigenous peoples, to which I claim no identity, felt more distant, but its academic tone gifted me with the vocabulary to examine my own family’s unspoken traumas and their effects on my life.

A and Z related in a similar way. They described their traumas in both personal and intergenerational terms. "You look at both of our upbringings, and there are different levels of emotional abuse on both sides," A said. "So it's very natural to behave in the same way, and I think we had to work really, really hard with each other just to learn how to effectively communicate despite these traumas."

They continued. "But there's also intergenerational trauma; all these mental health traumas that happened to my mom, and then which happened to me, and the trauma from my father's side of the family." They shared of a history of alcoholism in their family; commented on the appalling fact that Canada and the US’ last Residential Schools, which were effectively state-sponsored genocide, only closed in 1996; mourned the hundreds of years that Indigenous communities faced death and destruction; and dared anyone to try and say that all of that history didn’t affect Indigenous people today.

A is a registered member of The Little Traverse Bay Band of Odawa Indians, part of the larger Anishinaabe people, and though they have never lived on the reservation themself, their father did throughout different periods of his life. A’s has, in recent years, begun trying to strengthen relationships with other members of their tribe and to gather stories of their family’s history. They’ve often run into blocks: family members who refuse to talk about the past, others who don’t even acknowledge that they are Indigenous. But A persists, ardent that learning about their family’s truth can ensure their traumas don’t pass to future generations.

A with their father

When we first spoke in early 2021, A told me about their ambitions of running a non-profit in the future. When I asked about the details of their plans, they paused, sat up in their chair, and took a deep breath. "It is my goal to fucking destroy the entire American education system, because it's so flawed," they began. "Each group of people in the world have experienced periods of harm or genocide or oppression. But Native people as a whole have experienced continuous oppression, non-stop, to this day."

A's tone shifted. The doubt they allowed when talking about their own story was replaced with lucidity as they talked about the stories of systems and communities. "The way that we teach history in our country is fundamentally flawed. The American education system as a whole needs to be completely dismantled and rebuilt. The way that we teach the education surrounding Indigenous people in this country continues to perpetuate negative stereotypes, cultural appropriation and intergenerational traumas. If the only thing we teach about Native people is, 'You are nothing before Christopher Columbus, and then you were raped and murdered and slaughtered. Your people are extinct. You have no language. You have no culture.' What does that do to the psyche of the Indigenous person? What do you think we grow up thinking about ourselves?"

A’s work now attempts to combat these issues through development of a series of workshops for educators to help them teach about decolonization in the classroom. They also regularly organize mutual aid fundraisers, host boots-on-the-ground community work, speak at events, run workshops, and create both digital and physical art. They, along with Z and two of their friends, recently co-founded Outlaw Rising, an “intersectional NFT project vested in the rising of historically marginalized communities.”

Outlaw Rising’s homepage. Retrieved 12/

Z, too, talked about her personal connection to her family's multigenerational history. She spoke of enmeshment, “a description of a relationship between two or more people in which personal boundaries are permeable and unclear.” "When you are enmeshed with your family,” Z began, “your identity is completely tied to your family, and you're reliant on them as they are with you. You're codependent with your family, and that's sort of how a lot of East Asian people grow up."

She gave examples—the culturally driven values of filial-piety, respect for authority, and the expectation of caring for one's elderly relatives—and described the internal conflict she held of extricating herself from those values (to build her own identity) and entangling further within them (to honor her family and her culture).

A and Z (standing second and third from the left) with some of Z’s immediate and extended family

"I have been going through so much strife with my family," Z told me one evening, explaining the context for a conversation that she and A had been having between themselves. One of Z's family members, who’d been lobbing underhanded malice towards Z’s being queer, wanted to give her and A a few hundred dollars as a “gift” for the wedding. "She's not doing this because she cares about me or loves me,” Z said to A, her voice charged with irritation. “She's doing this to, like, save face with the family and show that she's a really caring and kind elder that should be respected.”

But in nearly the same breath, Z’s words turned with a form of optimism, a hope that she could still please her family and pretend to get along with them. "Dad's cutting off some cousins because we ultimately matter more, and I think that's great,” she said to A. “But I still don't want me being queer to have to affect anything. Which is super naive, right? Because all these problems are specific to me being queer."

Z with her father

Z took notice of a photo sitting in a small frame on the living room windowsill. It was a picture of her with one of her aunts. She looked at the photo for a few moments, pondering it. Then, she picked up the frame and took out the photo. "We recently found out that aunt is homophobic," she said. She replaced it with a picture of her playing in the snow with her mother.

Over the months before and after their wedding, A and Z have become some of my closest friends in life. We’ve spent over a month together now across five visits, their home in New Jersey becoming a physical and emotional base for me whenever I travel to the Northeast. But comfort forms only a part of why we’ve become so close. Equally important has been A and Z’s willingness to challenge my assumptions or views, and their patience while doing that.

Z, A and me on the wedding day

They first showed this during a video call before their wedding. I'd noticed the conversation moving towards their identity as queer people, and was curious to hear more about that part of their stories.

"What was that journey like for you?" I asked. A, gracious and patient with me throughout our friendship, nevertheless showed a certain annoyance at my word choice. If I didn't hit a nerve, I'd brushed against one. "I would definitely urge you to start asking straight people with the most serious face: 'Can you tell me about your journey as a heterosexual? What was that like for you?'" I squirmed in embarrassment.

They shuffled through a string of topics, each of which could be its own hours-long conversation: wanting to feel validation; internalized homophobia; their church's impact on their view of themself; the anger they felt during and after the Trump presidency; their efforts to force non-affirming people to acknowledge their existence and not ignore them.

Insofar as A and Z being queer is important to their story, it’s because of the way it changes how they move through the world, positively or negatively, as a result of that identity. The label itself, they said, plays no role in that. Like for any other couple, the love they share, not others’ opinions about that love, is what ultimately matters to them.

A and Z on their wedding day

"I was never confused about my right or ability to love somebody of the same gender," A told me. "You can call it lesbian, gay, queer, an abomination, whatever you want. But I'm good over here, and I think the labels can be really harmful in perpetuating stereotypes."

Z, too, talked about her feelings for A with burning certainty. "It didn't cross my mind for even a second that I shouldn't have introduced them to my entire family," she said. "It was only a couple of weeks after we met that I introduced them to my parents. I didn't think about anything else, because I was just so fixated on being with this person who made me feel everything."

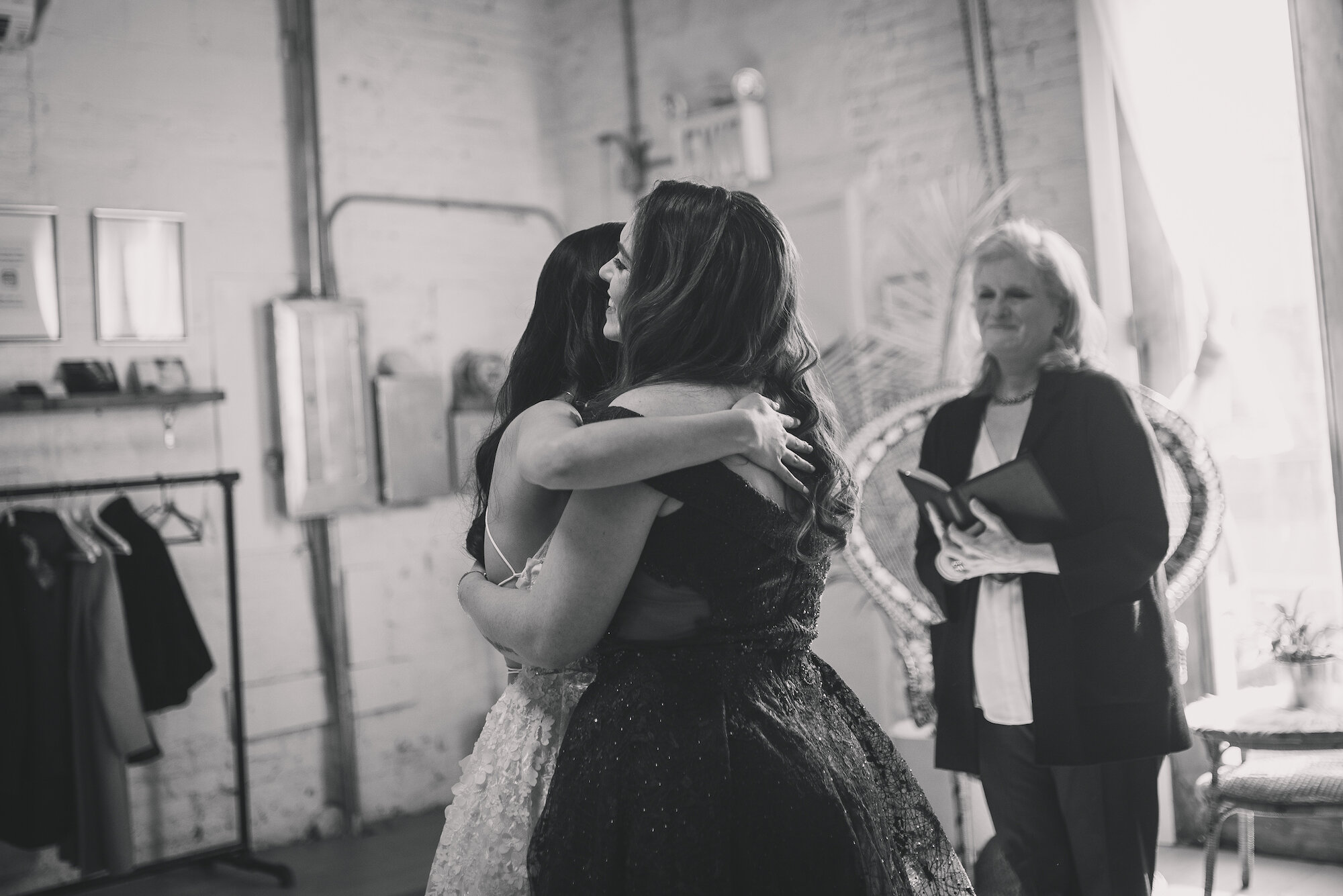

A and Z embracing after the ceremony

Her doubts came only when she felt the tight bonds of her enmeshment to family and culture. "The shame came later," she said. "I think only now am I facing the ramifications of being a queer Asian woman. Only now am I being ostracized from my family or becoming a topic of gossip."

She continued. "I've always wanted to be the one to uphold family traditions and Chinese culture. A lot of my cousins are ABCs"—American Born Chinese—"and they sometimes lean on me for translating between family members. And I love being that person; being able to connect people; being that bridge. But right now, I am living my worst fear, of not having that tether to my family. Who am I without my traditions? Who am I without my family?"

She recalled an early incident with of one of her aunts. "This aunt, she sees spirits and tends to know what's going on in your life. She does face reading, palm reading, all these different things. And she told me very early on in my relationship with A that they weren’t who I was meant to be with; that I wasn't queer; that I wasn't meant to be Harrison's parent. And honestly, that scared me for a really long time because of how superstitious I was, and how I felt that I had to follow a certain path."

"But, being so madly in love with someone, I couldn't help but just say, Fuck it. A's the most important to me. And as long as they’re happy, I'm okay."

A and Z together after their wedding

A and Z have a habit of turning their stories—happiness, trauma, all of it— into a form of cheerful banter that masquerades the difficult truths of life each continues to process. I often felt like a spectator to the playful game of catch that was their conversation.

Sometimes, their quips paint a comedic veneer over distressing social issues. One evening, as we talked about Residential Schools, A wondered aloud about the effects of their elders' traumas on their own life. Z cheerfully joked, "It's like they made you a Powerpuff Girl! Except the extra ingredient was trauma, and they accidentally put in whole thing."

Other times, their conversation suggests a unique form of love. One day during dinner, Z and A talked about each others' deaths. "It's like some weird type of hubris," Z said to A, "because I keep telling you, ‘Please, let me die before you, because I don't want to live a day without you in this world.’" A, laughing, added, "We probably talk about this too often, but I feel like if I die first, Z is probably going to die within a couple days of heartbreak." Comfortable at this point with poking fun at them, I asked, smirking, "And not the other way around?"

A and Z paused to look at each other and, as A slowly began to shake their head, the two burst into laughter. "They’re going to live for-fucking-ever!" Z said. "With or without me." A added to the bit, exaggerating their intonation and gesturing wildly. "Of course I'm not going to die if she dies. That's just stupid! "

After they laughed some more, A corrected themself, more serious now. "No, the truth is I will probably die if she died. But Vincent, if that happens, we need you to mention this conversation at one of our eulogies—" Z cut them off. "Both of our eulogies. You know, because we'll both be dead." A nodded, and said, "Yeah, right, right, we're gonna have a joint funeral."

They also have a charming sense of self-deprecation. When A commented that meeting Z had felt like a mystical, siren-esque experience, Z added, "Yeah, that's just the effect that I have on people." She quickly laughed at herself and deadpanned, "Just kidding. Absolutely no one ever has said that. I am widely regarded as... an awkward human."

Z covering her face in embarrassment after A made a joke

Another time, Z commented on Harrison's behavior in school, which placed him firmly in the "goody-two-shoes" category of elementary school society. "He was doing so well with a nervous tic he had, but ever since we started letting him go out to hang out with the neighborhood kids, it's been coming back. Maybe it's the stress of trying to fit in and be cool." A added, "Yeah I worry about him." They paused to think of ways to be helpful. "Who's the least cool person we know that can tell him it's okay to not be cool?"

Z replied immediately: “We are.” She and A broke into laughter. "We found each other! And now we're happy."

A and Z popping open a bottle of wine after their ceremony

"You and I have the same brand of crazy, you know?" Z said to A one day. "What more can you hope for in life?" After their months-long fights in late 2018 and early 2019, by April 2019, A was ready to propose again. (Proposal three.)

They coordinated with Z's family. One evening, as they all played the board game Life together, A waited patiently for Z to land on the STOP: Get Married space. When she did, Z's father took out a camera and A took out their ring, knelt in front of Z, and proposed through tears.

Z and A after the proposal

Z proposed back a few weekends later. (Proposal four.) Z placed a spoon into A's hot toddy one evening at home. A usually hated spoons in their tea and would immediately remove them, but for some reason, they left this one sitting for an hour. Z, nervous the entire time, finally asked if A was ever going to take the spoon out. When they did, they found that it was engraved: "A, will you marry me?" Z knelt down and proposed. A, of course, said yes.

Z and A at a small party they held after their proposals

A and Z’s original wedding date was in October of 2021, but with the uncertainty of the pandemic and their desire to begin the formal process of having Z adopt Harrison as soon as possible, they imagined how to downsize the event while keeping the values and people most important to them.

A told me about their vision in late 2020. "I think what we're hoping to do is to just have a courthouse wedding with our family and some of our friends, do all the traditional legal stuff and add in some Chinese traditions," they said. Z added, "A loves helping people, so I think we'd love to rent a catering truck and share meals with random people in New York who might need a meal. Get married at city hall and just hand out food for a day to people." (They ended up not having the truck, but did spend an hour after the wedding, in their wedding dresses, handing out food at a shelter in New York. They received many congratulatory shouts and claps from strangers.)

By 2021 early, just a few weeks before the wedding day, they’d planned almost nothing. A and Z were struggling with finances and their own emotions, exacerbated by their adopting a second dog, Darwin, a rescue who arrived with far more health and behavioral problems than the shelter had let on.

It wasn't until after the wedding that I learned about the extent of their stress. "Without that financial aspect of you photographing for free, we honestly would have never had a wedding. Really. We were struggling with Darwin and finding a way to be able to afford something. But we told ourselves that 'We have this one piece figured out: Vincent's photography. So let's craft everything else around that.' And we became more creative with our solutions and found something that turned out to be really beautiful."

Z and A exchanging rings

She continued, connecting her own experience to ideas with societal scale. "I think the most compelling piece to your project is the accessibility of beauty and happiness for those who may have less. But it's kinda also interesting to think about how people are trading vulnerability for a beautiful set of services on one of the biggest days of their life. Vulnerability in all senses: with their home by inviting you there; with their health during the pandemic; with their stories. And it's almost like an interesting sociological experiment, because people who have less will always be pushed to be more vulnerable in society, but you're crafting that vulnerability into something very beautiful."

A, Z and I on a vacation we took together in the fall of 2021

Just a few weekends before their wedding, A and Z descended into a frenzy of wedding-planning neurosis. The night was supposed to be a date, but over the course of the next 12 hours, A and Z found their venue—a small community-centered event space in Brooklyn called RE:GEN:CY, with a mission statement of, "We cultivate regenerative culture by providing education, resources, and a platform for community to flourish."—their food (a friend would make Greek) and their guest list (New York’s capacity limit mean they could only invite 12 people.)

A, Z and I woke up at 5am on the morning of the wedding to begin the two hour drive from New Jersey to Queens, where they'd be getting hair and makeup done a friend's chic apartment. A and Z were visibly exhausted. The two slept only a few hours the night before, having spent the night writing vows and cleaning their apartment to host a small reception after the ceremony.

A and Z exhausted the morning of the wedding

And still, the two found moments of levity. A brought a notebook to journal their thoughts, and its cover featured a large picture of Bernie Sanders. "Instead of flowers, what if I walked down the aisle with my Bernie Sanders notebook?" they joked, tucking the notebook under their arm and straightening their back in deference to their political spirit-candidate. Their hair and makeup artist, a woman named Pent, gave A and Z the regal looks they deserved for their wedding day, and her lively spirit lifted all of our moods.

We drove to the venue, threading our way through weekend traffic between Queens and Brooklyn. Inside, A and Z ducked into a changing room to put on their dresses together. Z's was white and fitted, with thin straps and an elegant open back; A’s was emerald green, strapless, billowy, and sparkling. (Their original dress was also white, but the seamstress in China they ordered it from became unresponsive a few weeks before the wedding. A spent a few frantic hours a week before the wedding desperately looking for an affordable dress that they still loved, and luckily found one.)

Public’s Make You Mine played over the venue’s speakers, and Z walked down the aisle with her father, her hand wrapped gently around his arm. She looked towards him with brimming love and admiration.

Z walking down the aisle with her father

Z gave her father a hug, and took her place next to the officiant as the song fell into one of its slower harmonies. A walked up the stairs and, upon seeing Z at the end of the aisle, gasped, quite audibly, "Oh, shit," their emotions suddenly overcoming them. They stepped down the aisle, and Z began to cry as A drew nearer. When A reached Z, the two shared a long embrace before holding each other’s hands and facing each other.

Z shared her vows first. "A... I literally fell for you on the day we met," she began, smiling. "Overeager to give you a parting kiss, I tripped over a curb and fell into you. And somewhere between my teeth crashing full-force into yours and my ankle twisting, you caught me with both arms. And that was that.”

“You have continued to catch me ever since. When I feel myself stumbling, you are always by my side, providing love and support when I need it most. I love you so, so much, and thank you for choosing me every single day."

She made a large sniff; a few tears were already running down her face. "To you, I promise to always grow alongside you. I promise to face all of our hardships as a team. I promise to fill your soul with comfort in times of sorrow. I promise to laugh with you in times of joy, even when my jokes slightly miss the mark. I promise you myself, and a life full of travel and adventure."

"And most importantly, I promise to break your falls too. I gotchu, in this life and the next."

Z's words left no dry eyes in the room, and A began her vows with their nicknames for Z.

"Bb wife! Honey-ah! Z!" They took a long pause to collect their emotions. "When we met, you stopped time." (Z's watch had stopped on their first date; she later gave the watch to A as a gift.) "A mystical, magical woman who smelled like leaves, lavender, and the summer sun. I was enamored by your beauty and your perpetual patience, and kindness towards plants. Your bravery and curiosity never cease to amaze me. At the time we met, you caught me off guard and balanced me in the same breath. You turned my world completely inside out. I'm honored and proud to be here with you today."

"From the beginning, so many things were easy, and so many things were hard. We made choices to learn each others' love language, and fight fair whenever we disagreed. We made plans, and followed through. In one of our first conversations, we decided to go to Paris together, and six months later we did. The point of all this is, when the world is ugly, and everyone bails, you're by my side. Since day one, you've been all in, and you haven't slowed down since."

"Today, and everyday, I'm proud of you, and so thankful that you are my partner in life, love and the pursuit of adventure. From our silly days, sad days, high days, and low days, I'm all in, and here for every bit of you. No matter what life brings us..."—A let out a soft gasp, just stopping themself from outright bawling—"I choose you. I choose us. I have since we met, and I always will. I love you."

They cried, and laughed; Z cried, and laughed with them. And everyone watching cried, and laughed with them, too.